|

"Words weave worlds beyond the page, Ink spills thoughts both bold and sage. A dance of rhythm, sound, and grace, Each line a mirror; time can’t erase. Writing lives where voices fade."

And that’s exactly what this article entails - how to write a good poem. We will discuss the main elements of the poem before diving into the step-by-step process of writing a poem. So, let’s rhyme in.

That being said, here are 3 definitions of a poem by famous poets. Poetry is when an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found words - Robert Frost. Poetry is the rhythmic creation of beauty in words - Edgar Allan Poe. Poetry is the spontaneous outflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origins from emotion recollected in tranquility - William Wordsworth. Before we expand on how to write a good poem, you should first understand the 3 main elements of a poem, that are rhythm, format, and literary devices. Let’s break down each of these for you.

Some poems have a steady beat, while others are free-flowing. It is created by stressed and unstressed syllables in a line or verse.

Consider this short verse: "Soft seas sigh and sliver sands gleam, Moonlight whispers in a twilight dream." Here, the repetition of the word ‘s’ sound mimics the gentle lapping of waves, making the lines feel smooth and calming. Poets use techniques like alliteration (repeated constant sounds), assonance (repeated vowel sounds), and consonance (repeated consonant sounds within words) to craft soundscapes within their poetry.

For example, in Shakespeare’s famous line from Romeo and Juliet: “But soft! What light through yonder window breaks?” This follows iambic pentameter, a meter where each line has five pairs of alternating stressed and unstressed syllables. Common meters include: Imabic (“ ‘): Words like ‘be-LIEVE’ or ‘a-LONE.’ Trochaic (‘ “): Words like ‘WIN-ter’ or ‘SUM-mer.’ Anapestic (“ “ ‘): Phrases like ‘in the NIGHT’ and ‘on the HILL.’

“He will not see me stopping here To watch his woods fill up with snow. My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near.” Here, the words “here” “queer” and “near” rhyme to create a flowing rhythm.

Where prose has sentences and paragraphs, poetry has stanza structures, line breaks, and patterns. This way, an artistic expression is created. For example, a quatrain (a four-line stanza) usually adopts an ABAB or AABB rhyme, which makes it easy to memorize (will be discussed below).

Metaphors: They compare two unrelated things, e.g., “Hope is the thing with feathers that perches in the soul.” Similes: They are used for direct comparisons and often use words like “like” and “as,” e.g., “as light as a feather.” Personification: It gives objects human traits, e.g., “the wind whispered secrets.” Onomatopoeia: These are the words that mimic real sounds, e.g. buzz, crash or rustle.

One may start with step 3, while the other may skip step 7 completely. Nonetheless, the steps mentioned here follow a logical flow to help you shape your poem from start to finish.

If you’re unsure where to start or don’t have a topic, try these methods: Read poetry: You can not create a poem if you’re not reading poems — it's as simple as that. Reading work by great poets can inspire the creation of ideas and help you understand different styles. Freewriting: This one’s interesting. Write whatever comes to your mind for 5 minutes without overthinking. You’ll be surprised at the ideas that get spit out. Use prompts: No, no, not AI prompts, but general inspirations and situations that give you a headstart. Think about a childhood memory, or your favorite place, the most interesting person you know, or even a dream you had last night.

"Two roads diverged in a wood, and I I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference." To develop a unique poetic voice, focus on themes that resonate with you. Ask yourself questions like “What emotions do I want my readers to feel?” or “What personal experience can I draw from?”

To see how form shapes meaning, here’s an example of the same idea written in two different styles: Limerick: “A poet once sat in the shade, Where verses and rhymes he had made. His thoughts danced around, In rhythm profound, Till ink on the paper has stayed.” Couplet: “A poet sat beneath a tree, His words as wild as the rolling sea.” Both convey the same idea — about a poet composing under a tree- but the limerick creates a playful, sing-song effect, while the couplet feels more lyrical and refined.

What is imagery? Well, it’s the use of descriptive language that appeals to the senses. For example, instead of saying, “The sun was bright,” you could write: “Golden rives of light spilled across the morning sky, Warming the earth with whispers of fire and gold.” And how about playing around with stanza structures? A short stanza can create urgency, while a longer one can feel more reflective. Let’s look at this example for better understanding: Short stanza: “The storm screams, Clouds collide, Thunder breaks the sky apart.” Long stanza: “The storm rolled in, a beast untamed, A symphony of thunder framed, By jagged streaks of silver light, That danced across the sky that night.”

We already discussed some of the literary devices above. A few other examples are shown below: Alliteration, where the consonant sounds are repetitively added at the beginning of the words, e.g. “The sun smiled down the sleepy town.” Symbolism, where objects or concepts are used to represent deeper meanings, e.g. “A withered rose symbolizes lost love.” The right literacy device can make your poem resonate with readers long after they’ve finished reading it.

AABB: The first 2 lines rhyme, and the next 2 do as well. “The stars shine bright (A) They light the night (A) The wind so free (B) It sings to me (B)” ABAB: Alternating lines rhyme. “The river flows with silver light (A) The birds above begin to sing (B) The moon emerges, shining bright (A) The gentle breeze begins to cling (B).” Did you notice the musicality in these? We bet you’re thinking about all those song lyrics you play on repeat. Yeah? A big part of why they get stuck in your mind is these rhyme structures.

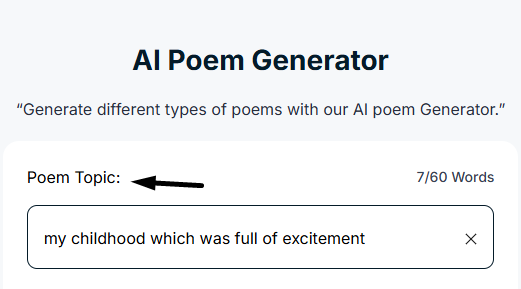

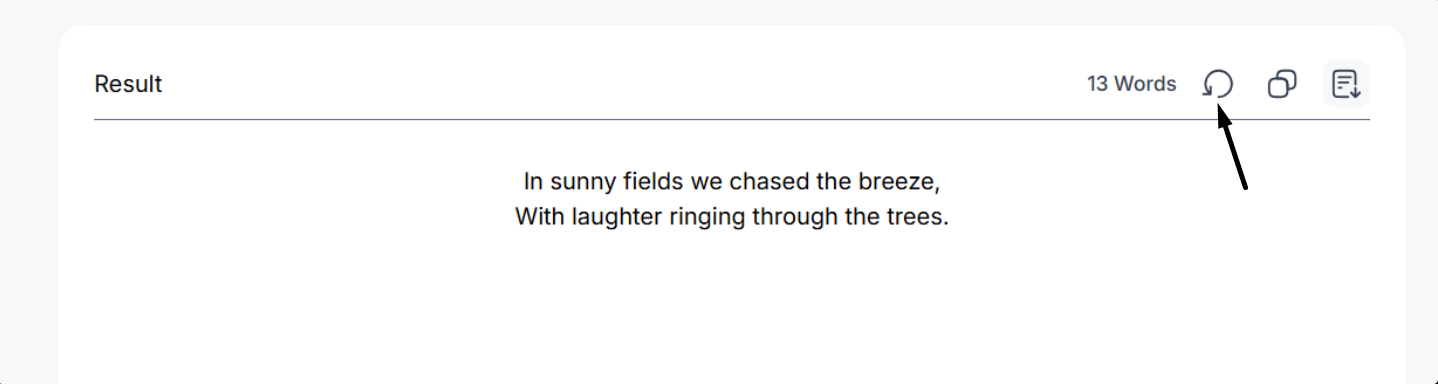

Trim unnecessary words. Poetry thrives on conciseness. Check rhythm and meter. Adjust awkward lines for a better reading and listening experience. Refine figurative language. Improve the metaphors and puns to fit perfectly in the theme of the poem. In this modern era, we can’t leave AI, right? It’s a tool that has and will make our lives better. But can it help you to write better poems as well? Or at least give you the inspiration you need in the case of writer’s block? Yes, tools like our AI Poem Generator can surely save the day for you. The process? Write the topic of your poem in the input box.

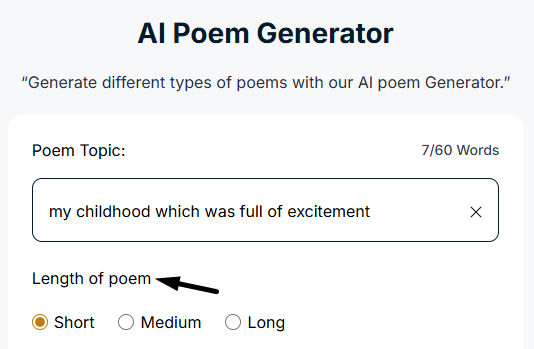

2. Select the length of the poem you want to create. You can choose from Short, Medium, or Long.

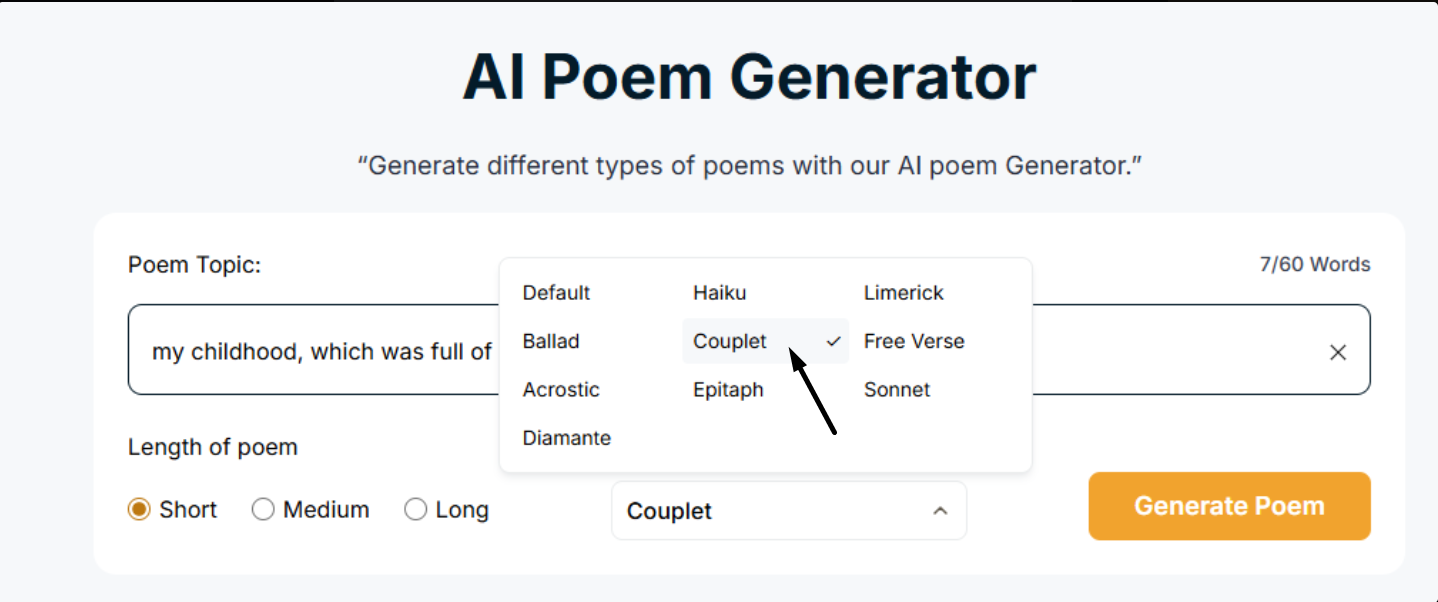

3. Now, select the poem format you wish for. There are 10 forms, including Acrostic, Epitaph, and Sonnet, to name a few.

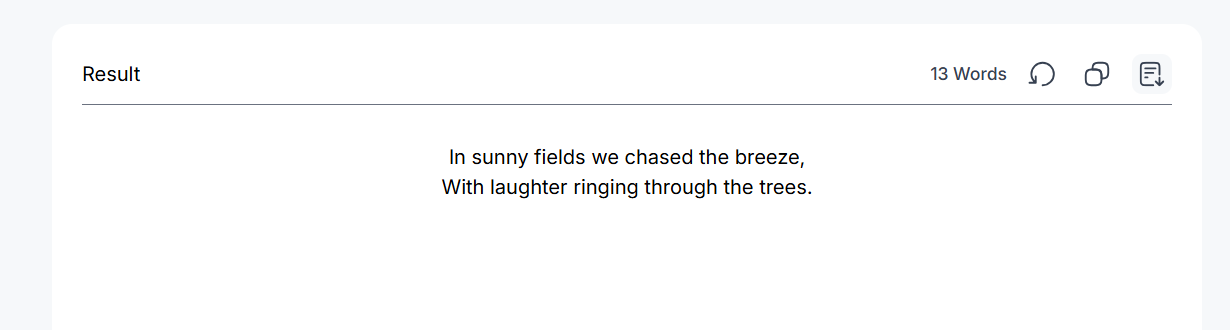

4. Click Generate Poem to get the desired poem within a few seconds.

5. You can click Regenerate for a different output as well.

Mastering how to write a poem is about balancing creativity with structure. From finding inspiration to adding imagery and literary devices (which we discussed in the article), each step shapes your poetic voice. With practice and passion, you will be able to craft words that move feelings and tell stories people love. How do I structure my poem? A poem’s structure depends on stanza length, rhyme scheme, and rhythm. You can follow traditional forms like sonnets, haiku,s or free verse, or create your own. Make sure to maintain consistent stanza structures, line breaks, and literary devices to enhance the flow and meaning of your poem, though. How many lines are in a stanza? A stanza can have any number of lines. It depends on the poem’s form and the poet’s intent. Common stanza types include: Couplet (2 lines) Tercet (3 lines) Quatrain (4 lines) Cinquain (5 lines) What is a line break in a poem? A line break is where a poet ends one line and starts another. It controls the rhythm, pacing, and emphasis of the poem. Poets use them to create pauses, shift meaning or enhance imagery. In free verse, line breaks replace punctuation for dramatic effect, while in structured poetry, they follow a set of rhythm. (责任编辑:) |